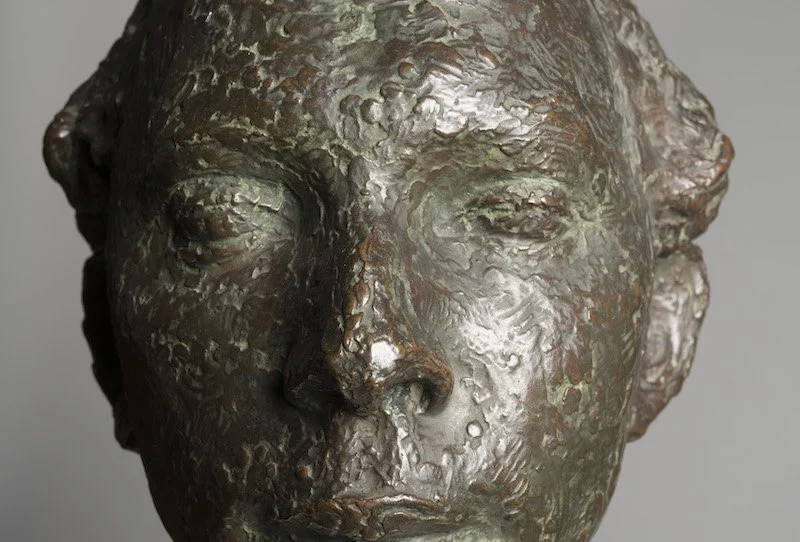

Barnett Freedman by Sam Rabin Collection Doncaster Museum Doncaster City Council © Estate Sam Rabin

The Re-discovery of Sam Rabin’s Barnett Freedman Bronze

In 1928 Sam Rabin had finished art school. He was very determined to become a full-time sculptor but this was not the first time he had felt so focused. As a young child he wanted to be the strongest man that ever lived and by eleven he thought he was! Now he found himself returning from Amsterdam having competed in the summer Olympics for wrestling. In his palm was a cold, heavy object the color of golden brown. He had won a Bronze medal at his first and only Olympics. This was even more incredible to imagine because at the time it was an amateur sport where athletes could not promote themselves and many were self-funded even going into debt. This was illustrated by his need to return and start working before the end of the closing ceremony. He was the only wrestler to win a medal representing Britain in 1928 so he missed this important affirmation of this incredible achievement.

When Sam returned to Britain he wrote to his close friend Barnett Freeman. They were both second generation Jewish refugees. Although they had unpredictable beginnings they shared the same intense struggle to become self-financing artists. Sam had received his first commission to carve one of the four winds believed to be from classical mythology on 55 Broadway in London. This would be the new Headquarters of the London Underground. After the First World War this was a building for the modern age with new ideas, expression and moving away from the past Victorian ideas. He relied on Barnett to contact the stone mason while he was away. Feeling relieved to be back in London and eager to start carving the letter said he returned “In one piece.” This statement is loaded with conjecture. Sculpture and wrestling were not complimentary activities. Injuries could have prevented him from achieving success with his first commission. He was a risk taker born out of a necessity to earn money and to take every opportunity that was available for him to develop his art.

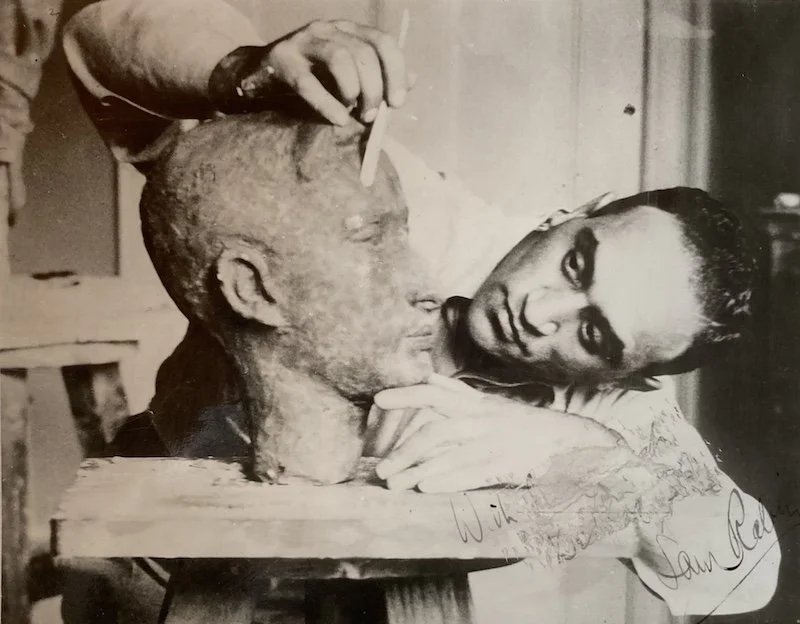

The same year he produced a striking bronze head. This would be incredibly expensive to cast at the beginning of a career. The person he chose was Barnett Freedman. Being a perfectionist so much of his work was destroyed so he must have worked and reworked the head until he was completely satisfied with the likeness and quality. This was illustrated by a newspaper article produced a few years later. The bronze of Barnett Freedman had been bought by the Contemporary Art Society CSA and stored in the imposing Tate Gallery. Sam was now struggling financially so to fund his sculptural commissions he became a professional wrestler. He said in a newspaper article that wrestling matches were not just for entertainment but risks were taken and wrestlers got angry. He said “ Maybe they’ll put it on show when I am killed in the ring.”

There was a storm surge that engulfed London embankments and basements the same year as the Amsterdam Olympics and when the Barnett Freedman bronze was created. Fourteen people drowned as the waters flooded the cellars where they lived and many more became homeless. The Tate had stored the Barnett Freedman bronze on behalf of the CAS in the basement. Looking at the position of the Tate it was dangerously close to the Thames embankment so there was no barrier as the water flooded the voids where the artwork was stored. In all the confusion and chaos some art perished as they tried to save the most precious pieces. Sam must have searched for his bronze perhaps years later when he had the funds to bring it out of storage and exhibit it for the first time. The feelings of anguish must have been devastating when he discovered it was gone, reluctantly concluding it was lost in the flood.

After the flood the surviving CAS objects continued to be kept at the Tate. There was no record of the Sam Rabin bronze. In 1963 the remaining CAS collection was redistributed to other museums the same year a bronze head was donated to Doncaster Museum as an unattributed artist. There it stayed for sixty two years. It was not until sometime later that the family of Lydia Lopokova believed the bronze had a strong resemblance to their relative who was a famous ballerina. The bronze was renamed Lydia Lopokova by Stephen Tomlin.

In 2024 my research on the life and work of Sam Rabin led me to contact Tania Adams a Collections Information Officer. We then started a dialogue about the missing Barnett Freedman bronze. Initially Tania sent the background story of the CAS objects stored at the Tate before and after the flood of 1928. I discovered the bronze had not been located in the intervening years. They had no photograph of the head so I sent a copy for their reference from the Retrospective Exhibition Catalogue which was also included in Bill Crow’s Book. Then came the astonishing response Tania said she had found it! It was in Doncaster Museum. This was ninety six years after it was lost! The bronze finally had a new title “Barnett Freedman by Sam Rabin.”

His close friend Stanley Paine was elated with the discovery because he had been looking for the bronze since he knew of its existence. It was very important to Sam especially as his close friend Barnett Freedman had died so young at the age of 56. He had one remaining wish….. that Sam had been alive to see it!

By Sharon Taylor 2026

References

Bill Crow “Sam Rabin”

The Evening Standard Saturday July 21st 1934

Stanley Paine

Tania Adams Collections information Manager for CAS

Doncaster museum Neil Gregor

Making the Head of Ewan Philips